Articles

Shariah Compliant Equity Investments: An Assessment

1. Shariah Compliant Equity Investments: An Assessment

M.H. Khatkhatay

ABSTRACT

The preferred Islamic investment format is equity. However equity comes along with ownership. Hence Islamic investors have to ensure that the selected company’s activities and structuring are not repugnant to shariah norms. Due to exigencies of modern business and particularly the pervasiveness of interest transactions, fully shariah- compliant equities are extremely rare.

So, shariah scholars have arrived at minimum compliance criteria which, while excluding companies in gross violation, yet provide investors a reasonably wide choice of shariah-compliant equities.

The authors have reviewed and compared the norms set by three organizations. A critical and analytical assessment of the different criteria follows. Empirical data of the five hundred companies included in the BSE500 index of the Bombay Stock Exchange is used to assess the impact of the different norms.

Based on the empirical results and analytical arguments and in the backdrop of an Islamic perspective, an independent set of norms is proposed.

1.0 INTRODUCTION

When investing in any avenue, Islamic investors need to take into account not only the structure of the transaction but also the nature of the counter party. An investor in the share capital of a company becomes technically a part-owner of the company and therefore responsible for its internal structuring as well.

As a result, in case of investment in equities traded on the stock exchanges, the investor needs to consider further issues of the company itself being involved in shariah non- compliant financing and structuring. Due to this, initially shariah scholars tended to completely rule out investment in listed equities. Over time however, realisation has seeped in that a more balanced view needs to be taken.

For one, the general prevalence of conventional banking operations makes it inevitable that but for a miniscule percentage, all businesses have to transact with banks in some way or other and, to some extent at least, rely on interest-based finance. Secondly, portfolio investment in equities on the stock markets is a convenient and often the main investment avenue open to ordinary Muslim investors and it is also close to the ideal Islamic profit and loss sharing paradigm for financing.

Hence, the consensus is now veering towards accepting a degree of compromise in the definition of shariah-compliant business. The shariah boards of various organisations, official regulators and market intelligence providers have put forth various criteria to define the maximum degree of compromise which could be considered acceptable under shariah, given the current business environment.

The norms set by Dow Jones, USA, SEC, Malaysia and Meezan, Pakistan to screen businesses for shariah compliance have been considered in this paper. The norms of these three institutions have been mutually compared and assessed critically in an objective fashion, keeping in mind the normal relationships between various items on the balance sheet and profit and loss statements of a company.

The published data of the companies included in the BSE-500 index of the Bombay Stock Exchange for the years ended March 31st 2001 to March 31st 2005 has been used to

provide an empirical back-drop to the discussion and to assess the relevance and degree of stringency implied in each of the three sets of parameters.1

On the whole the SEC’s criteria appear to be the most liberal and that of Dow Jones the most conservative. The use of market capitalisation in the screen ratios by Dow Jones (and also in some areas by Meezan) has been questioned as not being apt. In the screens for level of debt and level of interest earnings, it has been shown on theoretical grounds as well as from the statistics cited, that the defined levels of acceptability tend to be on the liberal side and need to be tightened. The commonly used screen for level of receivables is shown to have little relevance to the actual objective sought to be achieved by the screening.

We have presented in this chapter an overview of the whole paper. Chapter two delineates the data base used as well as the research methodology employed. Chapter three discusses the importance of equity investment in the field of Islamic investment and also highlights its associated disadvantage from the shariah aspect. The paper points out that in view of the importance of equity investment, shariah scholars have permitted some compromises with shariah requirements (in the public interest i.e. Maslahah). These compromises imply setting maximum reasonable limits to the concession allowed.

Chapter four delves into the rationale and nature of the concessions that need to be made. Chapter five presents the sets of criteria laid down by the three different institutions studied, as mentioned above. Chapter six compares the different sets of criteria mutually and in relation to the empirical data of the 500 companies included in the BSE-500 Index of the Bombay Stock Exchange and comments on the relative stringency or licence permitted by the various organisations on each count. Chapter seven critically evaluates the various sets of criteria objectively and studies their implications in relation to the empirical data cited. Chapter eight summarizes and reports the findings of the study.

2.0 DATA BASE AND RESEARCH METHODOLOGY

As mentioned earlier, the basic rationale behind formulating screening norms is to provide Muslim investors a reasonably wide choice of selection of shariah compliant equities, till such time other fully shaiah compliant investment options become widely prevalent.

Hence, any screening norms stipulated have to be assessed in relation to the universe of listed equities available in the milieu. In this paper, the selected sets of norms are studied in the context of the Indian stock market.

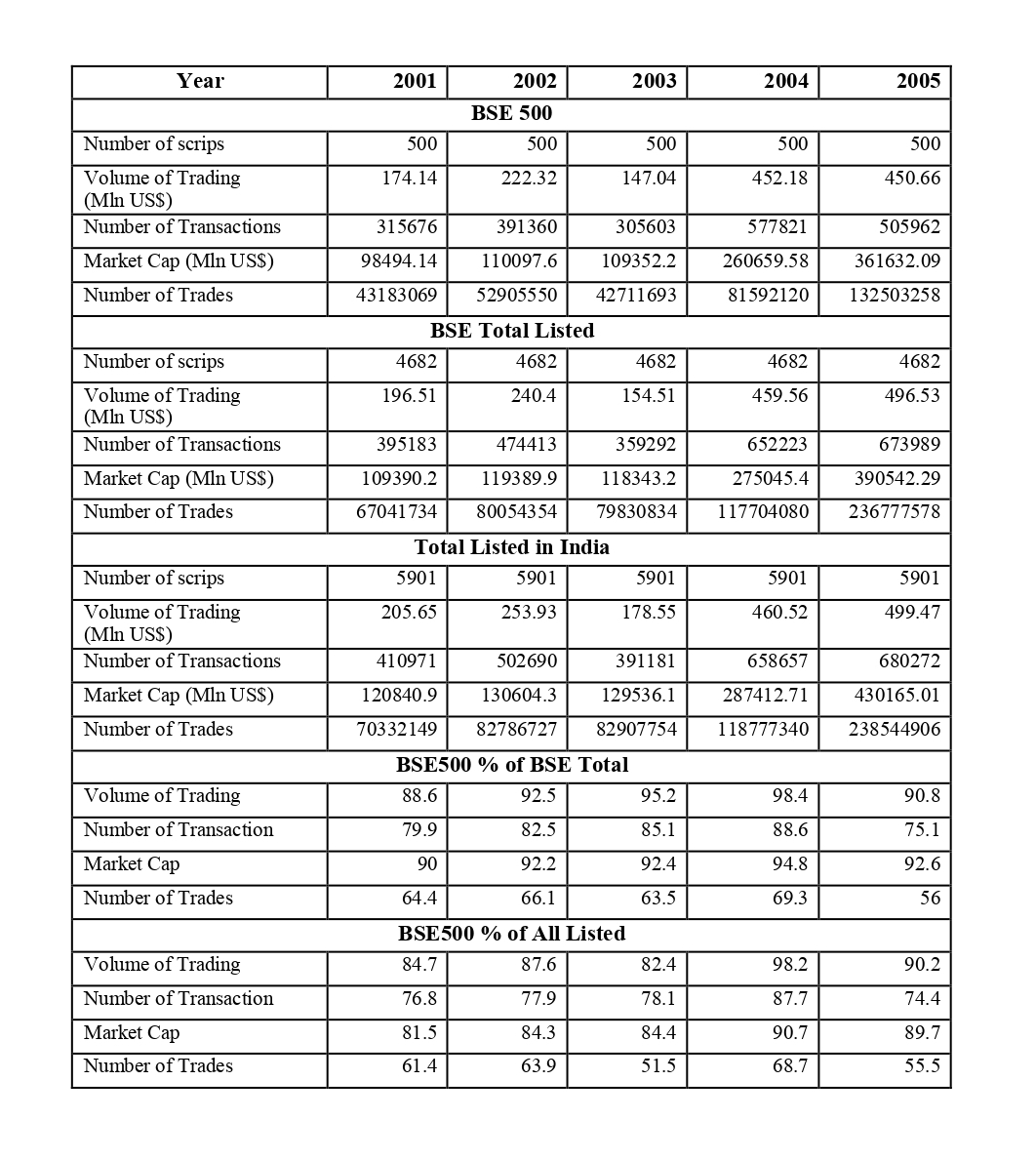

In terms of trading volumes and number of listed scrips the Bombay Stock Exchange (BSE) has a preeminent position in the country closely followed on certain parameters only by the National Stock Exchange (NSE). This is borne out by the statistics presented below.

In terms of trading volumes and number of listed scrips the Bombay Stock Exchange (BSE) has a preeminent position in the country closely followed on certain parameters only by the National Stock Exchange (NSE). This is borne out by the statistics presented below.

Thus share trading in India is dominated by the BSE and NSE. The three bellwether indices for the Indian stock market are the BSE Sensex; the BSE 500 index and the S&P CNX Nifty.

The first of these tracks a mere 30 scrips listed on the BSE and the last S&P CNX Nifty 50 shares quotes on the NSE whereas the BSE index, which we have chosen, is based on a sufficiently large yet manageable 500 from the BSE.

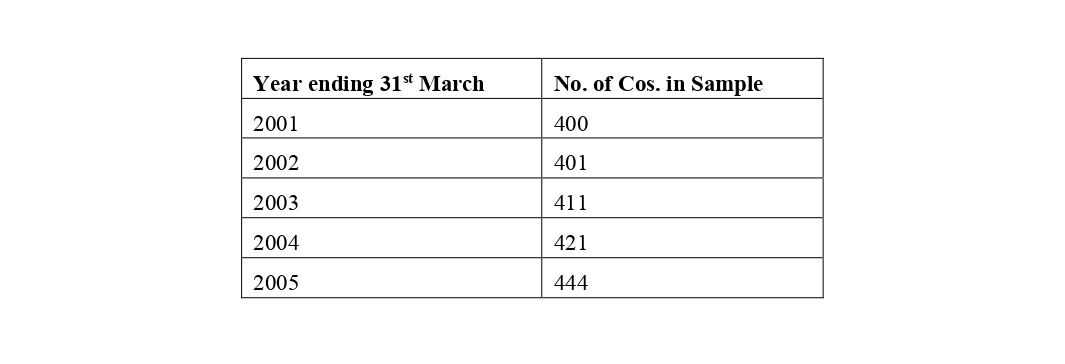

Hence, data for companies included in BSE500 index is used in this paper for studying the selected screening norms. The overall period selected is April 1, 2000 to March 31, 2005. Data for the selected period was obtained from the database of the Centre for Monitoring Indian Economy (CMIE), a prestigious private sector data base provider which counts India’s top corporates as well as the country’s central bank, the Reserve Bank of India (RBI) among its clients.

The database provided covered accounting (balance sheet and income & expenditure) data as well as average market capitalization for each of the companies included in BSE500 index over each of the twelve-months periods included in the overall period. As banks and other financial institutions such as non-banking finance companies, housing finance companies etc. are heavily involved in interest based transactions, such companies have been excluded from the 500 index scrips. Further, certain accounting figures appear as denominators either in the screening norms are in the ratios used in the analysis, some scrips from the BSE 500 index have been excluded as one or more of such accounting figures for them in one or more of the years covered were less than zero or unavailable. This has mainly been either on account of listing in later years or negative income or net worth in some years.

Apart from the exclusion as above, no other companies have been excluded from the BSE 500 population on the grounds of non-shariah compliant (other than substantial interest earnings) activities.

All data used was designated by CMIE in million US$ using the relevant INR/USD conversion rates as per the RBI norms.

All data used was designated by CMIE in million US$ using the relevant INR/USD conversion rates as per the RBI norms.

3.0 EQUITY SHARES AND EQUITY FUNDS AS SHARIAH-COMPLIANT INVESTMENT AVENUES

In assessing whether a specific investment proposal is compliant with shariah stipulations, it needs to be examined from two angles, i.e. the nature of the instrument / transaction itself and the nature of the contracting (counter) party. For instance a trading transaction can be considered from two aspects:

a) whether there is any gharar, riba etc. involved in the structuring of the transaction, and

b) the nature of the counter-party (business).

While examining a transaction for riba, gharar etc is done as a matter of course, the same extent of systematic attention is perhaps not devoted to examination of the aspect of whether it would be correct to deal with a particular counter-party, which has an interface with (an organization or enterprise carrying on) a haram activity.2 The commercial transaction by itself is not unlawful. But it involves associating or providing goods or services at a price, to an individual or institution engaged in a haram activity. Such association in some of the instances cited above may not be a regular occurrence, but may comprise a varying proportion of the regular business activities engaged in, ranging from a minor or negligible portion to being the sole activity. Under such conditions is it

permissible under shariah to transact with such a party, even if the structuring of the transaction itself is valid.

3.1 EQUITY SHARES

In case of investment in equities, the structuring of the transaction itself appears unobjectionable as equities do not confer any assured benefits on the holder. In fact the shareholder could even stand to lose his entire capital in the event the company in which he has invested suffers massive losses.3 Nor does equity investment necessarily involve the element of randomness and uncertainty associated with gambling and games of chance. The rights and obligations of the parties too are clearly defined and do not involve exploitation or injustice.

There could however be a problem as far as the nature of the counter-party’s (i.e company’s) business itself is concerned. As holder of equity shares, the investor is the owner of the business – though only part-owner. As an owner, the holder of equity is responsible for any infringement of shariah by the company. However, as a minority shareholder (the usual case), he cannot realistically expect to influence the policy of the company as to the nature of its business and how it carries on its business. Both these can change too over time and breach shariah stipulations.

At the same time, in many different milieus share investment represents a viable major (in some cases only) non-interest based investment avenue for sleeping investors. Moreover, with the modern advances in computing, communications and information dissemination, even lay investors can now easily invest on the stock exchanges. Globally, we find many countries (including those wherein Muslims form a majority or a substantial portion of the population) where there is negligible presence of credible organizations offering Islamic banking and investment options. At the same time they have a thriving and well- organized and regulated sector of listed equities or equity-based mutual funds.

In the absence of sufficiently safe and pure modes of genuine profit-sharing avenues, equity markets represent an important investment alternative that is close to the Islamic profit-and-loss-sharing investment ideal. Ruling them out leads both individual investors as well as Islamic financial institutions to turn to spurious barely disguised and hard-to-

digest fixed return modes of investment and financial leases, many of which are just the same old debt-financing methods merely garbed in Arabic terminology.4

Further, in modern times the sectors of listed companies and mutual funds are fairly closely monitored and regulated by the authorities with the objective of obviating accounting manipulation and financial malfeasance, thereby assuring the ordinary small investors of a reasonable protection against being cheated -- something he cannot hope to assure for his investments on his own.

There is therefore a strong element of maslahah in permitting equity investment under shariah, provided the nature of the business and the way it is carried out are such that even in case there is a violation of shariah stipulations, it is kept within certain limits. The permission could be conditioned on the absence of sufficiently prevalent and credible Islamic investment alternatives in the given environment.

3.2 EQUITY FUNDS

Equity funds or equity-based mutual funds are the financial institutions which mobilize investments from the public against the units of their fund and invest all these funds in listed equity shares. Thereafter, they calculate the NAV (Net Asset Value) of the fund units on a daily basis and may allow investors to exit or enter the fund at or around NAV. The fund may declare dividends periodically and even liquidate itself at a certain stage and pay off the investors on the basis of the final break-up value of the units. The expenses of the fund and the remuneration of the fund manger are defrayed from the earnings of the fund. A mutual fund unit thus closely resembles an equity share in that it too does not guarantee any fixed returns to the investors or an assurance of return of any part of the initial investment.

In addition, it gives the investors the benefit of a diversified investment portfolio and the services of expert investment advisors, in spite of a modest investment outlay. The downside for him from an Islamic point of view is that his investment goes into shares of a large number of companies engaged in different businesses and with varying types of financials, over the selection of which he has no control, except to the extent the offer document of the fund defines the investment policy of the fund.

Thus, though the investor can normally ensure (by selection of the right fund) that his money is invested only or overwhelming in equities, he cannot be certain that all the companies in which his money goes are in permitted businesses or have financial structures which are shariah compliant.

4.0 THE BUSINESS AND STRUCTURE OF THE ENTERPRISE

In judging the shariah compliance of the counter-party (the company invested in) one has normally to consider the nature of the business it is engaged in. However, when the transaction is one of investment in equity, the investor is also responsible for the way business is structured.

4.1 BUSINESS OF THE ENTERPRISE

The shariah categorizes certain commercial activities as impermissible or haram for Muslims.5 Hence investment in the shares of any company engaged in such haram activities as its main business, is clearly impermissible under the shariah. There would be instances of business firms which are not primarily engaged in haram activities. As part of their operations however, they may indulge in activities which are not permissible according to shariah.6 Alternatively, a firm involved in a permissible activity may have a subsidiary or have an investment in another company, which may be involved in non- shariah compliant businesses.

The most conservative ulema do not permit investment in the equity of a company which is invested in haram business to any extent.7 Others allow investment in equities of companies which derive a minor part of their income from haram activities, provided such activities are not their main area of interest.8 Yet other ulema agree to such

relaxation only if the same can be justified on grounds of masalahah i.e. public interest. Yet others make an exception if the haram activities are so pervasive in the society as to be a commonly prevalent evil, difficult to avoid.9 An instance of the former may be the serving of alcoholic drinks in planes of a national carrier, whereas earning interest through treasury management is an instance of the latter.

4.2 STRUCTURE OF THE ENTERPRISE

While studying the structure of the business from a shariah viewpoint the three aspects that need to be considered are:

a) debt availed by the company;

b) interest and other suspect earnings of the company;

extent of cash and receivables with the company.

c)

4.2.1 Indebtedness of the Enterprise

In the modern world, most organized businesses rely on banks to part finance their activities. Partly this is due to the need for fluctuating working capital and ready availability of bank capital for financing and maintaining ongoing trade and its expansion in the face of unforeseen exigencies of business. Such exigencies include natural calamities, political and industrial relations developments and disputes, business slowdowns and recessions, sudden fluctuations in costs, prices, availability and demand, etc. all of which could lead to an unexpected snarling up of the business cycle and draining out of liquidity from the business. In such situations, banks ease liquidity pressures by providing the additional working capital required by the enterprise. Apart from working capital needs, banks also finance acquisition of fixed assets in case of major expansion and diversification of business.

Due to fluctuating conditions it becomes almost inevitable for even a moderately-sized enterprise to access bank capital, at least for working capital purposes. This is accentuated by the fact that with Islamic banking in its infancy, there is often no viable Islamic alternative to bank capital. But bank finance is interest-based and therefore, haram. Hence, while investing in these equities and becoming part-owner of such a company may be, strictly speaking, against Islamic norms, the principle of masalahah may permit

some degree of flexibility and allow investment in equities of companies in which debt is below a certain level.

The measure conventionally used to assess the level of indebtedness of a company is the debt: equity ratio. There is no reason the same ratio should not also be used to assess the indebtedness of the company in terms of its compliance with the shariah. And indeed many institutions do use it in such a context. Alternatively, one can use the related ratio, debt: total capitalization. Now some institutions use the ratio, debt: market capitalization.10

4.2.2 Earnings from Impermissible (Haram) Activities

Banks play a major role in facilitating transactions in modern times. All cash flows of the enterprise are routed through banks. As a result all businesses have to maintain accounts with banks. These accounts attract some nominal interest. In addition, at times enterprises have to keep security deposits with banks and others to cover performance-guarantees and assurances. These accounts too fetch the enterprise some interest.

The enterprise may also, at times when it is flush with funds, deploy excess short-term liquidity in bank deposits and securities as a measure of treasury management. For an outsider investing in the equity of an enterprise, it is difficult to judge, whether, and to what extent interest accruing to a company is inadvertent and involuntary and to what extent planned and deliberate. It is not feasible to expect the investor to investigate this aspect.

At the same time, to ensure that the interest-earnings of a company do not substantially contribute to its revenue, it is essential to set certain limits to the proportion of interest- earnings to the total revenue of the company. For this purpose, the measure used is interest (and other haraam income) earned as a percentage of total revenue (income). Various shariah boards fix this percentage at different levels, generally between 5% and 15%.11

A further, aspect of shariah compliance on this score involves removal or facilitating removal of the interest component from the earnings of the company, either by the

company itself or (more often) by providing the necessary information to the shareholders. For the latter purpose, the company also includes in the ratio communicated to the shareholders, (if applicable) any earnings received from any other shariah non- compliant activities, such as for instance, sale of alcoholic drinks in a hotel or resort.

4.2.3 Cash and Receivables/Payables of the Enterprise

Finally, there is the shariah stipulation that cash and debts cannot be traded except at par value. It appears that in applying this ruling to the valuation put on a company’s shares, the shariah scholars have considered a company as the bundle of assets and liabilities (reported on its balance sheet), including fixed assets, investments, cash, inventory, receivables, payables and debts. The traded price of its equity can hence be considered as representing value paid for the underlying assets and liabilities. If the fixed assets and investments of a company are negligible (as happens for trading companies), then the remaining assets and liabilities mainly comprise of debts, deposits and stocks. In equity trading, the price of scrips traded is driven by future expectations of prices and not by the book value of the company. Hence, if stocks (inventories) are valued at market prices, one can end up with a residual value for the cash and debts of the company which can be way out of line with their par values.

As a result, it would be unacceptable shariah-wise to be involved in the trading of such scrips. To minimize the possibility of landing in a flagrantly non-compliant situation of this nature, particularly if the equity is being publicly traded, most shariah scholars like to place a limit on the proportion of current assets in the total assets of the company.

The measure or parameter most commonly used to judge compliance on this score is percentage of current assets or receivables or net current assets to total assets (or total capitalisation) of the company. Alternatively, the numerator can be net receivables instead of net current assets. The cut-off value of the parameter is usually set in the range of 40 % to 50 %.

5.0 SCREENING NORMS FOR SHARIAH COMPLIANCE

As mentioned earlier, different Islamic banks, investment companies and equity funds have their own norms for assessing shariah compliance of companies in which they

consider investing. Most such organizations do not publicize the norms they use for selection or screening of the companies. Organisations such as Islamic Development Bank, the Association of Islamic Banks, AAOIFI, IFSB and the Islamic Fiqh Academy of the OIC also have not laid down any definite criteria in this regard.

On the other hand, information is available on the screening criteria used by Dow Jones for inclusion and tracking of equities (listed at various stock exchanges) in its Islamic equity indices. Similarly, the screening criteria used by the Securities and Exchange Commission, Malaysia are also available as is the criteria used by Meezan, Pakistan.12 Unfortunately, the rationale for adopting a particular norm by each of them is not known. The criteria used by these organizations are described in the section below.

DOW JONES ISLAMIC INDEX SCREENING CRITERIA13

5.0.1 Screens for Acceptable Business Activities

Activities of the companies should not be inconsistent with shariah precepts. Therefore, based on revenue allocation, if any company has business activities in the shariah inconsistent group or sub-group of industries it is excluded from the Islamic index universe. The DJIMI Shariah Supervisory Board established the following broad categories of industries as inconsistent with shariah precepts: alcohol, pork related products, conventional financial services (banking, insurance, etc.), hotels, entertainment (casinos/gambling, cinema, pornography, music, etc.), tobacco, and weapons and defense industries.

5.0.2 Screens for Acceptable Financial Ratios

After removing companies with unacceptable primary business activities, it removes companies with unacceptable levels of debt or impure (interest) income by applying the following screens:

5.0.2.1 Debt to Market Cap

Exclude companies for which Total Debt divided by Trailing Twelve Month Average Market Capitalization (TTMAMC) is greater than or equal to 33%. (Note: Total Debt =

Short-Term Debt + Current Portion of Long-Term Debt + Long-Term Debt).

5.0.2.2 Liquid Assets to Market Cap

Exclude companies for which the sum of Cash and Interest-Bearing Securities divided by TTMAMC is greater than or equal to 33%.

5.0.2.3 Receivables to Market Cap

Exclude companies if Accounts Receivables divided by TTMAMC is greater than or equal to 33%. (Note: Accounts Receivables = Current Receivables + Long-Term Receivables).

Companies passing the above screens are qualified to be included as components of the Dow Jones Islamic Market Index.

5.2 SCREENING CRITERIA OF SECURITIES AND EXCHNAGE COMMISSION (SEC), MALAYSIA14

Screening for shariah complaint stocks is done at central level by the Shariah Advisory Council (SAC) of the Securities and Exchange Commission (SEC). A list of permissible stocks is issued by the SAC twice a year. The screening criteria are mainly activity or income based. No debt or liquidity screens are used. Thus screening requires income statements but not the balance sheets of the companies. Individual funds or investment companies do not make their own shariah screening criteria. Following screening criteria are used:

5.2.1 Core Activities

The core activities of the companies should not be shariah incompatible. Therefore companies with following as their core business activities are excluded: Financial services based on riba (interest); gambling; manufacture or sale of non-halal products or related products; conventional insurance; entertainment activities that are non-permissible according to shariah; manufacture or sale of tobacco-based products or related products; stock-broking or share trading in shariah non-approved securities; and other activities deemed non-permissible according to shariah.

5.2.2 Mixed Activities

For companies with activities comprising both permissible and non-permissible elements, the SAC considers two additional criteria:

a. The public perception or image of the company must be good; and

b. The core activities of the company are important and considered masalahah (in the public interest) to the Muslim ummah (nation) and the country, and the non-permissible element is very small and involves matters such as umum balwa (common plight and difficult to avoid), uruf (custom) and the rights of the non- Muslim community which are accepted by Islam.

5.2.3 Benchmarks of Tolerance

Applicable in case of mixed activities. If the contributions in turnover or profit before tax from non-permissible activities of a company exceed the benchmark, the securities of the company are classified as shariah non-approved. The benchmarks are:

5.2.3.1 The Five-Percent Benchmark

Applied to assess the level of mixed contributions from the activities that are clearly prohibited such as riba (interest-based companies like conventional banks), gambling, liquor and pork.

5.2.3.2 The Ten-Percent Benchmark

Applied to assess the level of mixed contributions from the activities that involve the element of ‘umum balwa” which is a prohibited element affecting most people and difficult to avoid. For example, interest income from fixed deposits in conventional banks.

5.2.3.3 The Twenty Five-Percent Benchmark

This benchmark is used to assess the level of mixed contributions from the activities that are generally permissible according to shariah and have an element of maslahah (public interest), but there are other elements that may affect the shariah status of these activities. For example, hotel and resort operations, share trading etc., as these activities may also involve other activities that are deemed non-permissible according to the shariah.

5.2.4 Debt and Liquidity

No restrictions on the proportion of debt or proportion of liquid assets in total assets.

5.3 MEEZAN ISLAMIC FUND CRITERIA, PAKISTAN15

It undertakes investment in Equities, Mudarabahs, Islamic Sukuks, and other shariah- compliant fixed income securities. The shariah screening criteria for equities and other securities is given below:

5.3.1 Business of the Investee Company

The basic business of the Investee Company should be halal. Accordingly, investment in shares of conventional banks, insurance companies, leasing companies, companies dealing in alcohol, tobacco, pornography, etc. are not permissible.

5.3.2 Debt to Total Assets

The total interest-bearing debt of the Investee Company should not exceed 45% of the total assets.

5.3.3 Net Illiquid to Total Assets

The total illiquid assets of the Investee Company as a percentage of the total assets should be at least 10%.

5.3.4 Investment in Shariah Non-Compliant Activities and Income from Shariah

Non-Compliant Investments

The following two conditions are observed for screening purposes: The total investment of the Investee Company in shariah non-compliant business;

i. should not exceed 33% of the total assets and

ii. the income from shariah non-compliant investment should not exceed 5% of the gross revenue. (Gross revenue means net sales plus other income).

5.3.5 Net Liquid Assets vs. Share Price

The net liquid assets (current assets minus current liabilities) per share should be less than the market price of the share.

6. COMPARISON OF VARIOUS SCREENING NORMS

6.1 COMPARISON OF SCREENING ACCORDING TO NATURE OF BUSINESS

A detailed comparison of the three sets of screening norms given in the previous chapter is instructive. Dow Jones has provided an exhaustive list of different types of industries which its shariah advisory board has classified as non-compliant. We shall use that list as the primary list for comparison. There is some unanimity regarding the industries considered as shariah non-compliant. Convergence of views for screening on basis of nature of business is only to be expected since the shariah compliance of an industry is mostly directly deduced from the injunctions of the Holy Quran and the Hadith. Thus, all the three sets of norms include industries engaged in the business of (conventional) finance and insurance, liquor, non-halal foods, entertainment and gambling in the list of prohibited industries. The Dow Jones list also includes the industries of Hotels, Broadcasting & Media, Defense and Real Estate and Property Development among the non-compliant industries.

SEC of Malaysia explicitly allows investment in companies with mixed businesses16 It has screening norms for such companies too. If such companies have a “good image” and their core activities are considered maslahah then such companies too can be accepted if their incomes fall within set (income screening) norms.

It has three parameters here: a basic parameter applied across the board, accepts those companies whose income from non-compliant activities is less than 5% of the total income. The second parameter, allows a higher tolerance level of 10% for this ratio in case of income arising out of generally prevalent activities that are difficult to avoid (umum balwa) in a particular industry,. The third parameter lays down a still higher tolerance level of 25% for the ratio in case of companies whose business has an element of masalahah on account of that industry being in the interest of Muslims or the country, impinging on rights of non- Muslims, etc.

Meezan too does allow, though indirectly, some leeway to companies with mixed activities. It accepts companies as shariah-compliant if;

a) its investment in non-compliant business is less than 33% of its total investment,

and

b) its income from non-compliant activities is less than 5% of its total income.

Dow Jones on the other hand, apparently, indirectly makes an exception only in the case of interest earnings. It accepts a company as shariah-compliant if the ratio of its cash and interest based securities to TTMAMC is less than 33%. (This ratio is discussed in detail in the next chapter).

From the above it can be deduced that though Dow Jones is more stringent in excluding other non-compliant activities, it is quite liberal when it comes to interest-earning activities. Then comes Meezan. SEC Malaysia appears to be the most liberal.

SEC screening criteria also has a subjective element in that it allows mixed businesses if the company has a “good public perception” and core activities are considered maslahah. Such subjective criteria are not advisable.

6.2 SCREENING ON THE BASIS OF FINANCIAL RATIOS

Some ratios used for screening companies by the three organisations have been already discussed in the preceding section on screening by nature of business. This is because those ratios were related to the nature of business of the unit. SEC, Malaysia does not use any ratios other than those earlier discussed. Dow Jones and Meezan on the other hand have screens relating to other criteria. These are the level of indebtedness of the unit, the level of receivables or total or net current assets and the level of interest income.

6.2.1 Level of Indebtedness

Dow Jones sets the acceptable level of indebtedness at less than 33% of market capitalisation, whereas Meezan puts it at 45% of total assets.

Considering the BSE 500 index data and applying the Dow Jones and the Meezan screens to the data we find that:

a) The aggregate borrowings vary between US$ 43701 million in 2001 to US$ 55707 million in 2005, aggregate total assets correspondingly vary between US$ 140128 million in 2001 to US$ 246574 million in 2005 and the aggregate market capitalisation varies between US$ 119994 million in 2001 to US$ 269790 million in 2005.

b) As the ratio of aggregate total assets: aggregate market capitalization is mostly (except for 2005) greater than 1.0 (varying from a high of 1.63 for 2002 to

1.09 for 2004), the cut-off level (of 33% of market cap) of the Dow Jones criteria is more conservative than the Meezan criteria (of 45% of total assets).

c) Even for 2005 (for which the above ratio is 0.91), since the Meezan criteria ratio is 45% whereas the Dow Jones is only 33%, in spite of the lower total assets to market cap ratio the Meezan criteria is still almost 25% more liberal than the Dow Jones one.

d) The mean deviation of total assets values is lower than that of the market cap values. As a result even in 2005, though the aggregate of total assets at US$

246.59 billion is lower than that of market cap at US$ 269.79 billion, still the number of companies individually qualifying on a screen of 33% (at 294) with respect to total assets is 16% higher than that (at 253) with respect to market cap.

e) Consequently the number of companies qualifying on the Meezan criteria is consistently higher (312 to 378 -78% to 85% of the sample) than the number qualifying (152 to 253 - 38% to 57% of the sample) on the Dow Jones criteria.

Hence it can be concluded that the Meezan criteria is by far much more liberal on the factor of indebtedness than the Dow Jones criteria.

6.2.2 Level of Receivables

Currently the Dow Jones index sets the acceptability limit for the ratio of receivables to market capitalisation at 33%. Earlier its limit was 45% and the denominator was total assets instead of market capitalisation. It also stipulates another ratio, i.e. of cash and interest-earning securities to market cap with a ceiling of 33%, presumably to put a cap on the level of liquid assets.

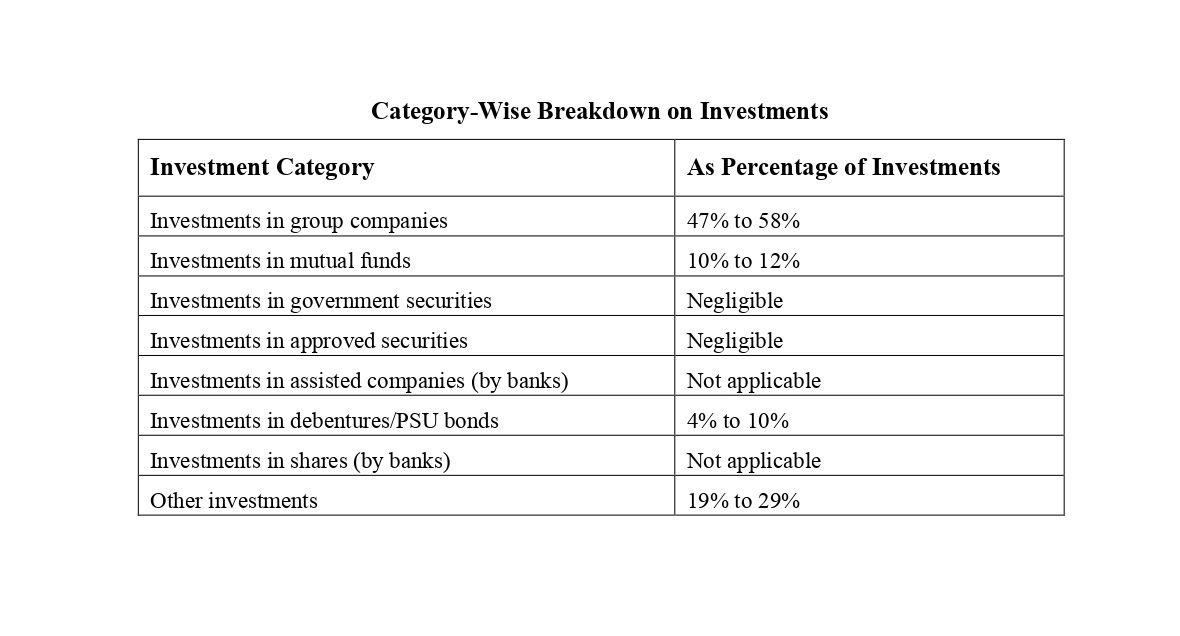

As against this, Meezan assesses the liquid assets on the basis of two screens: one using the ratio of total liquid assets to total assets with a cut-off value of 90% (i.e., minimum 10% for illiquid assets) and the other using the ratio of net liquid assets to market cap with a cut-off value of 100%. Classification of data with CMIE does not give a clear breakdown of investments into interest bearing and non-interest bearing investments, as

well as into liquid and illiquid investments. Instead the available classification of data gives the breakdown of investments into other categories. The different categories and the percentage of investments in each category over the period of study is given below.

From the above it can be seen that the categories drawing the bulk of the investments are “group companies” and other “other investments”. It is not clear what part of these investments is interest-earning and what part is liquid. Investments in group companies could be in the form of shares or loans, similarly mutual funds invested in may be growth funds (equity based) or income funds (securities based). This latter category of investments will however, be liquid.

From the above it can be seen that the categories drawing the bulk of the investments are “group companies” and other “other investments”. It is not clear what part of these investments is interest-earning and what part is liquid. Investments in group companies could be in the form of shares or loans, similarly mutual funds invested in may be growth funds (equity based) or income funds (securities based). This latter category of investments will however, be liquid.

Apart from the “investments” head, the other account head which gives the quantum of liquid and/or interest –earning funds is “cash and bank balances”. The bulk of these comprise fixed (time) deposits with banks which earn interest but can be withdrawn at short notice, albeit with some loss of interest. However, the ratio of “cash and bank balances” to “investments” varies from 0.44 to 0.61, i.e the quantum of “cash and bank balances” is only about half of that of “investments”. Hence the only definite conclusion that can be drawn is that the 4% to 10% in “debentures/PSU bonds” is interest-earning, and the 10% to 21% in mutual funds liquid.

In view of the above it is not possible to exactly quantify either the ratios for the companies studied on the basis of aggregate values, nor to know as to how many companies qualify on the basis of the relative screens using ratios based on liquid investments or interest-earning investments. As a result the only ratio that can be assessed on the basis of the database is the Dow Jones ratio relating to receivables.

Comparing the two sets of criteria and using the BSE 500 data, gives the following empirical findings:

a) The aggregate values for receivables vary between US$ 37.38 billion to US$

60.79 billion.

b) As we have seen in the previous section, a ratio using 45% of total assets in the denominator is much more liberal than a ratio with 33% of market cap. Hence, the change in the parameter has made the Dow Jones screen for assessing level of liquid assets more conservative.

c) Though it is not possible to exactly quantify the ratios involving liquid or interest-earning investments or securities, it can still be deduced that the Meezan criteria of liquid assets to total assets is more liberal than the Dow Jones criteria of Receivables to market cap as even the ratio of “cash and bank balances” plus “investments” (liquid as well as illiquid) to receivables is consistently lower than 1.0 (varying between 0.5 and 0.9.

d) Comparing the parameters used by Dow Jones and Meezan, we find that on the criteria of liquid assets too, Meezan is more liberal than Dow Jones.

e) The only criteria that can be applied to the companies in the BSE 500 set is the Dow Jones one involving receivables. On this criteria between 101 companies (in 2002) to 263 (in 2005) qualify.

7.0 CRITICAL ASSESSMENT OF VARIOUS SCREENING NORMS

Norms for screening equities are used by different sets of users. These could include portfolio managers, providers of market intelligence and regulators. Different users have different objectives and hence the screening norms they use reflect their objectives. Thus the primary concern of portfolio managers is likely to be to select a portfolio of shares that provides a good return on their assets. Here again, depending on the underlying objectives, whether of high growth, steady income, low risk, high risk etc., different portfolio managers may have different screening norms. Managers of Islamic portfolios will add to their normal (commercial) objectives the objective of selecting shares which are likely to conflict less with shariah stipulations -- in the real commercial world, a fully

shariah-compliant business is rare.

Similarly, organisations which provide index information will have their own norms. Their concern is primarily to provide a feedback about the overall state of the market. Hence their selection criteria and weightages are likely to be in favour of the more intensely traded and higher market cap stocks. Their intention is to provide investors a measure to judge the current state of the market as against that prevailing on an earlier day or that likely to prevail in the future. Their indices also enable investors to assess how a particular stock is doing in the market in relation to the overall market. Hence the primary measure for them is the market price of the share and therefore the market capitalisation. The higher the market capitalisation of a share, the greater its importance to them. Then, if the idea is to provide an Islamic Index, they need to add some shariah- compliance criteria to weed out those companies which deal in non-shariah compliant products/services or function in non-shariah compliant ways.

Market regulators would need to identify those shares which show suspicious, irrational movements such as sudden spurts in trading volumes or upward or downward movement in prices or sustained bouts of dumping or selling by interested parties beyond limits set by regulations, etc.

The objective of such regulators is to ensure a healthy and steady development of the market without sudden and wild swings and to enable it to grow in terms of depth as well as number and diversity of scrips offered. At times national policy may also dictate promotion or curtailment of certain industry segments or holdings by certain type of investors. In such a situation, the market regulator may monitor those industry segments or investor types and provide appropriate regulatory concessions or safeguards to promote the policy objectives.

On the other hand, when we consider defining screening norms to identify shariah- compliant equities, our concern has to be to select those stocks from the share market universe which function within the minimum realistically acceptable deviations from shariah stipulations, keeping in mind the nature of the environment. Thus the focus of such screening norms has to be on selecting shares which meet the above objective.

Including in the screening aims promotion of companies such as “good companies”, companies promoting “green” practices, healthy or fair labour relations, etc., or those

companies likely to provide reasonable returns, safe investment, etc., is misplaced. For that is not the objective of screening norms to identify companies meeting shariah stipulations. Certainly honest dealing and fair practices are the sine qua non for any civilized society and generally all nations have suitable laws to address the need to ensure that such practices prevail. It is not for formulators of Islamic investment screening norms to look at those areas or dilute their focus on that account.

The other important point regarding Islamic screening norms is the nature of compromise with Islamic stipulations they accept. Certainly in the current increasingly globalising business scene, there are many areas in which business is likely to be facilitated or promoted by adopting prevailing business practices. This does not however mean that in every case, a business which does not embrace such practices, cannot be viable. The compromise has to be kept to that minimum without which the business would be unviable, or grievously hinder the national interest.

7.1 SCREENING NORMS REGARDING NATURE OF BUSINESS

There would probably be a consensus among scholars that the primary screen for identifying shariah-compliant businesses has to be about the nature of the business. No extent of compliance with shariah otherwise can substitute or compensate for a falling off from compliance on this issue. Hence the norm in this regard has to be sufficiently stringent.

Among the non-permitted areas documented in the available literature relating to the three organizations considered in this study, the list given by Dow Jones is the most exhaustive and may be considered quite comprehensive.17

Among the industries included in the list, the rationale for excluding real estate holding and development is not readily apparent; probably it is due to the generally high levels of leverage prevalent in the industry. Comparing the Dow Jones list with the list of non- compliant industries considered by Meezan and SEC, Malaysia, we find three notable omissions as compared to the Dow Jones list in the lists of the others. These are defense, hotels, broadcasting and media.

It appears that the Dow Jones criteria has resorted to extra caution resulting in not letting through even some shariah-compliant units in an industry if most units in that industry may not be compliant. Hotels and media and broadcasting for instance, do not have anything intrinsically objectionable about their activities. However, as a prevalent practice hotels do serve non-halal foods and alcoholic beverages. Similarly, media coverage and broadcasting may include material with nudity or obscene images. Not all food wholesalers and retailers too may trade in non-halal food items. However, for a provider of market information it may not be easy or feasible to obtain and keep abreast of such details about operations of specific units in such industries where most units tend to be shariah non-compliant.

Probably the better solution would be to have a more exhaustive list of industries as Dow Jones has, which automatically excludes all units figuring on the list. Then have a secondary list of industries from the excluded list, from which specific units could be included in the permitted (shariah-compliant) list if specific information from time to time indicates that it does not indulge in objectionable practices. The onus for providing such regular updates could be placed on the reporting units themselves and the same could be periodically or randomly audited by the screening and certification organizations for a suitable fee.

There are also some important omissions in the Dow Jones list, going by the apparent logic of their selection. These are air and sea passenger transportation. Most units in these sectors serve alcoholic drinks and non-halal foods to their patrons. If hotels are on the excluded list, it is difficult to understand why air and sea passenger transportation are not excluded as well. Further, these industries usually operate with exceptionally high leverage too.18

In the case of the Dow Jones criteria, once “a company has business activities in any of the sectors (in the prohibited list)”, it is considered inappropriate for investment. This is as it should be. Meezan and SEC, Malaysia, however, do not adopt this approach. For them it is the main or core business which should not figure in the excluded list. A unit with main business interest from the permitted list and a minor interest in an industry

from the excluded list is still permissible, if the operations in the non-shariah compliant area are of a minor nature.

It is difficult to see the justification for making such exceptions, except if it be to artificially increase the universe of shariah-compliant equities. If this be so, it does not appear to be a sufficient cause for the departure from norms.

Another area that needs to be addressed is investment in associate or subsidiary companies. A company’s own business may be shariah-compliant. But it may have investment in associate or subsidiary companies which are in shariah non-compliant sectors. In such an event the parent company would also need to be excluded. Probably one may need to make an exception only in case the investment is of a short term nature or as a measure of treasury management.

7.2 SCREENING NORMS RELATING TO FINANCIAL RATIOS

The companies short-listed on the basis of nature of business have to be further screened on certain financial parameters. Essentially the financial screening is necessary for three reasons according to most shariah scholars (none of them really with anything to do with the financial performance of the company). These are:

a) due to the paucity of alternative Islamic modes of financing available, the reliance of almost all companies on interest-based borrowings to part finance their business;

b) the pervasive nature of interest-based transactions in the modern economy, leading to the inevitability of all businesses having to deal with banks for various purposes including short-term treasury management, keeping fixed deposits with banks in order to avail of bank guarantees and issue letters of credit, maintain cash balances with banks to facilitate transactions, etc.

c) the prohibition of exchanging debts and cash at other than par values.

Thus the screening on the basis of financial ratios is also directly or indirectly a corollary of the prohibition of interest-based transactions. These screens can be categorized as:

a) Screen for level of debt financing

b) Screen for level of interest earnings

Screen for level of receivables.

c)

7.2.1 Suitability of Market Capitalisation for Use in Screening Ratios

For the different screens used, ratios of various financial terms are used. One of the financial measures used to assess the value of ownership of a company and used in some screens, is market capitalization.

Dow Jones uses market capitalization as a denominator in all the ratios it uses for screening. Meezan too uses it for one of the ratios it uses (for screening for liquid assets,

i.e. receivables, primarily). Which financial terms and what kind of ratios are to be used should follow from the objectives sought to be gained. But does market capitalization fit the bill.19

It is claimed that market capitalization gives the true worth of a company and hence it needs to be used as a basis for the financial ratios. While such a contention is far from the truth, even if that was the case, its use in all the ratios is not relevant or appropriate for some of them have nothing to do with the worth of the company. It needs reiteration that use of a specific term or ratio depends on the objective for which that term or ratio is being used.20 Then again, fundamentally screening norms need to focus on the company itself and its activities and assess them on objective criteria. How the market perceives a company is not relevant to the Islamicity of its activities. The market price of the share is not the amount invested in the companies assets; it is the price settled for the share of the company by buyers and sellers independent of the company.

Also, it is almost impossible to sell or buy all the shares of a company, on the stock exchanges in a few days or even a month. The final price (even average price) of the shares being sold or bought over the period of purchase or sale could be vastly different from that prevailing when the exercise was initiated.

There is also often no definite rationale behind the way share prices fluctuate. The only definite statement that can be made about price movements on the equities market is that

they are largely driven by sentiments about future earnings and movements. What creates those sentiments on a particular day is a different matter. It could be past performance, news of current performance, expectations of future results, market manipulations, a result of demand-supply imbalances, government policies, political developments, international price movements, even the state of health of a national leader or finance minister or even the holding of a major match of a sport the nation is fanatical about.

Thus, often in the span of a few weeks or a couple of months, the share price of an equity share can skyrocket or nosedive. The IT boom and bust of a few years ago is a case in point. In a wild jacking up of share prices, new IT start-ups with no revenue stream to talk about (leave alone a profit stream) reached astronomical heights only to plummet back to the price of scrap paper. Even ignoring such extreme scenarios, it is not unusual to find over a year’s interval share prices rising to more than double or sinking to les than half their original values, when there is no apparent change in their underlying fundamentals.

A practical problem of using market capitalization also is that with sudden market movements, a company which was considered shariah-compliant one day, has to be considered shariah non-compliant the next day, if there is a downward price fluctuation. As a result Islamic investors would have to compulsorily exit, leading to further downward pressure on its price, thus destabilizing its price. Similarly an opposite movement could lead to a corresponding (though more muted) upward move too. And all this with no change in the company’s operations. Such market destabilization would also be an unhealthy and wholly avoidable consequence of involving market capitalization in the screening norms.

7.2.2 Norm for Level of Debt Financing

Unlike Dow Jones (which uses debt: market capitalization as its measure), Meezan uses the ratio of debt: total assets. This is a more rational approach. In fact it was the ratio used by Dow Jones too earlier. It gives a measure of how much of the operations of the company are being financed by the shariah non-compliant debt component. Such a ratio therefore clearly follows from the objective sought.

There is however a problem with the level at which Meezan has set the permissibility parameter. The cut-off value of 45% appears too high. Normally as a thumb rule, any well-managed company is supposed to aim for a debt: equity (i.e net worth) ratio of 1:1,

and a current ratio of 2:1. This translates to a cut off value of 40% to 42% for the Meezan ratio, assuming the current liabilities plus provisions: to total assets ratio is 15% to 20%.

However this is conventional financial wisdom which requires companies to consciously rely on moderate debt levels to leverage profitability. While selecting Islamic screening norms, we need to set the tolerance levels on the basis of how much debt could be unavoidable. The ideal ratio is 0:1.

Shariah scholars tend to plumb for a debt: equity ratio of 30:70 or 33:67 (equivalent to a debt: total assets ratio of 24% to 28%) on the tenuous argument that in a certain instance the Prophet (peace and blessings of Allah be upon him) is reported to have said: “one- third and one –third is too much”. Though one-third may be considered a reasonable minor proportion for some matters, such as voting on important issues, probably for the debt: assets ratio it should be lower. We must remember, we are making concessions and the actual ratio should be zero.21 The concession should be mainly based on working capital requirements (i.e. for financing net current assets).

Considering the BSE 500 aggregate data, we find that the net current assets: total assets ratio works out to an average of 12.8% (varying between 16.9% and 11.1%) and the Debt: Total Asset ratio to an average of 26.2% (varying between 31.2% and 22.6%). This implies that the investment requirement for net current assets is about 13% only whereas the actual borrowing is about twice of that. The balance of the borrowing is being used to finance a part of the fixed assets of the companies. It is to be noted that the percentages quoted are based on the aggregates of a sample of companies operating in a conventional manner with no inclination of avoiding debt. For those looking for companies operating close to Islamic norms, the ratios should be far more stringent.

At the same time we must accept that companies differ in their capital structuring, depending on the sector in which they operate. There may be a case for setting differential ratios for the debt: total assets ratio depending on the industry segment. If this is not feasible, a debt: total assets ratio of <20% or 25% appears a realistic tolerance limit to be set. The lower limit is 50% higher than that required for financing the average net current

assets and the higher limit about 50% higher than that required for financing the higher end of net current-assets.

7.2.3 Level of Interest Earnings

Compliance with shariah requires completely abjuring lending of money on interest. While the infringement involved in borrowing on interest is mitigated on the count of need, the earning of interest cannot be absolved except that it be of an involuntary nature and the same is to be further compensated by donating any such involuntary earnings of interest to charity. In view of the above, any interest earnings in the business have to be of a purely incidental and marginal nature.

As interest can only arise if there is an investment in interest-earning assets, it is obvious that the basic control parameter has to be the investment aspect. Meezan’s approach therefore in having an independent screen to control investment in non-compliant assets apart from the screen for non-compliant income, is therefore well-conceived. It must be noted however, that we do not accept their unstated assumption of permitting mixed businesses and therefore allowing investment in and income arising from non-compliant activities. Our submission is that the only non-compliant activity from which income can accrue is interest-based investment.

The single Dow Jones screen which can be linked to level of interest earnings also focuses on the investment aspect rather than the income (it does not stipulate a separate screen for interest income). Its screen is based on the ratio of cash and investment in interest-based securities to TTMAMC. This screen is really for screening liquid assets and therefore not suitable for screening out companies on the level of interest income (or for that matter, level of interest earning assets). As interest can accrue on assets which are not necessarily securities, we think the absence of a separate screen for interest income in the Dow Jones set is a grave omission.

As far as the levels of exception being made by Meezan and Dow Jones are concerned, they appear to be very liberal and not at all justified either on the basis of the underlying rationale for permitting such exceptions nor indeed even on the basis of the actual situation prevailing in the business environment.

As we have seen earlier, and needs to be reiterated all the time, the parameters laid down in the screens are only to alleviate the inevitable hardships for operation of businesses or

to present sufficient choice for Muslim investors in selection of equities from the stock market, keeping close to Islamic norms. Normally the margin of return to companies in their core business is several times the return they can expect to make on short-term investments on interest. At the same time, to meet with the essential Islamic requirement of eschewing the earning of interest, we can only permit a short-term (preferably involuntary) investment in interest-earning avenues, as an adjunct to and as incidental to a core halal business. In view of this, the proportion of assets permitted to be invested in interest-earning avenues cannot be allowed to be more than 10%.

With such a proportion of investment in interest-bearing assets and a rate of return from those assets several times below that from the assets in compliant (core) business, the proportion of interest in the total income of the company cannot be higher than 3%.

Thus the two screens used by Meezan should have been set at 3% and 10% rather than 5% and 33% respectively.

Coming to an empirical validation of our recommendation, the BSE 500 aggregate data shows:

a) Interest: total income ratio varies from 0.93% (in 2001) to 0.64% (in 2004).

b) With a screen ratio of 5% for this criteria almost 94% to 98% of the companies qualify whereas with a ratio of just 1% still 72% to 81% qualify.

c) As discussed earlier, separate figures for interest-earning investments are not available in the database. Making allowance for non-interest earning investments, such as in equities of associate companies and subsidiaries in growth oriented mutual funds and strategic and portfolio investments, it appears reasonable to assume that the investment in interest-earning assets is likely to be a minor (25 % to 40% say 33%) part of the total investments. Adding to this, the amount in bank deposits, the ratio for interest-earning investment to total assets is found to vary from 6.0% in 2001 to 7.2% in 2002 & 2003, 8.6% for 2004 and 13.9% for 2005.

d) As the proportion of cash in the “cash and bank balances” aggregate figures is quite minor (varying between 4% and 12%), the ratio for the Dow Jones criteria of cash + interest earning securities as % of market cap is also not likely to cross the

10% level except in 2005. Hence the Dow Jones benchmark for this screen too appears too liberal.

e) On the basis of the Dow Jones parameters, (assuming interest-based investments as 33 % of total investments), 87% to 97% of the companies qualify whereas on the Meezan screen relating to liquid assets (assuming 50% of total investments as liquid), all the companies qualify. Hence it may be concluded that both these screens are too liberal.

In the light of above discussion it is recommended that to assess shariah compliance on the level of interest income (no income should be allowed from other non-compliant activities), two screens should be used:

a) Interest income : total income (revenue) < 3%

Investment in interest-based assets : total assets < 10%

b)

7.2.3.1 Purging of Interest Income

For purification of income, i.e. purging of the shareholder’s share of interest, it is recommended that he should donate to charity the pro rata amount of interest income earned per share by the company for the period of his holding of the share, irrespective of whether the company pays a dividend or not. Such donations should be made preferably immediately on declaration of results; alternatively on receipt of the dividend.

The important point to be noted here is that the intention is to remove the entire interest earnings from the operations of the company to the extent to which the (Islamic) investor is concerned; not just to the extent of its impact on either the net profit or the dividend. Sometimes the amount to be purged is calculated as the amount of dividend multiplied by the ratio of interest income to total income. It will be obvious that this method only removes the interest income from the minor portion of the revenue which goes towards payment of dividend. Neither does it remove the component of interest income used for operations (to defray costs) nor does it remove the interest that goes into retained earnings.

Some scholars suggest that purification should also apply to capital gains realized on sale of shares, the proportion to be purged again being related to the interest (or non- compliant) income earned. We do not think this is necessary. For one thing, movement in

share prices are linked as earlier noted, to expectations of future earnings. These earnings (and therefore expectations) relate to the main activities of the company, not to the marginal income being generated by interest. Then again interest-based investments of a company cannot provide windfall gains as they are normally conservative types of fixed income investments, as bank deposits and short-term treasury-related investments. Income from such investments is already discounted on an ongoing basis in the share price prevailing and is in line with the present scenario. It cannot fuel substantial price movements. Hence according to the authors, notwithstanding the pious intentions of those arguing for such purification, there is no real justification for such a demand.

7.2.4 Level of Receivables

Both Dow Jones as well as Meezan stipulate certain maximum ratios of receivables or liquid assets as one of the screens for checking shariah compliance. Though detailed rationales for the screens used by the two organizations are not known, the rationale commonly given for stipulating a cut-off level for receivables has been discussed in section 4.2.3 earlier.

With due apologies to the learned scholars, it appears to us that their approach to this issue is based on a simplistic reasoning which does not take note of the relevant aspects involved. It is wrong to treat a company in the modern world whose equity is publicly traded as simply a bundle of accounting assets and liabilities, defined on its balance sheet. For a start, some very vital and valuable assets of the company may not figure on its balance sheet at all. Marketing assets such as brands, distribution networks and logistical arrangements, as well as licenses, quotas, permits, access to lucrative but protected markets, etc. do not normally appear on balance sheets. Even intellectual property such as patents, formulae, source codes of software, etc. are assets, which even if assigned a book value in terms of research costs are sometimes actually worth thousands of times more. Even fixed assets either appear at historical costs or are revalued only at infrequent intervals.

Then there are other intangibles such as the company’s public image, the value of key individuals in the company’s top management, marketing, production and research teams. An interesting pointer here would be the extreme manner in which the fortunes and values of the top soccer clubs fluctuate on their signing on or losing the top players in the game.

Similarly access to markets, raw materials, power and other utilities in times of shortages can impinge on the value of a company’s share price. Since here the argument concerns the value paid for a company’s share in relation to the composition of its assets and the value paid for a publicly traded equity is driven by market expectations of the future, there is no connection between the assets of non-negotiable value (as per shariah) and the market price. The market price movements do not, even in a minute way mirror the price assigned by the market to the company’s receivables, payables and cash balances.

Hence it can really be futile to place a figure on the share of a company only or mainly on the basis of its balance sheet assets. A company such as a trading company can have negligible assets other than receivables and payables, and some inventory and yet due to its intangible strengths it could command a huge premium in the market on its breakup value. This is not because it is able to sell its receivables and cash at a premium or liquidate its debts at a discount (as the reasoning of the shariah scholars requires). It is because of its inherent or intangible strengths.

Conversely, a company may own valuable real estate assets. As a result in the event of liquidation of its assets, the break-up value of its share could be several times its traded value, if it is not performing well. This is because the normal market players have a short- term investment horizon and know that the company management does not have an immediate intention of closing shop. Hence they view the company as a going concern and not as spoils to be shared out.

Hence the very basis for the stipulation regarding limiting the level of receivables appears to be misconceived and invalid. Of course, the Dow Jones stipulations being based on the market capitalization and therefore suffering the additional weakness inherent in using TTMAMC as a measuring quantity, is even more unsuitable than the Meezan criteria. However, the basic idea of using level of receivables to judge shariah compliance is itself flawed and irrelevant.

8.0 CONCLUSION

To summarise, the paper has shown that the screens commonly used to assess shariah compliance of companies for the purpose of including them in the list of acceptable companies, need to be modified.

The nature of business of the companies considered acceptable has to be fully shariah – compliant. A company with multiple businesses with even a minor shariah non-compliant business, needs to be considered as unacceptable. Similarly a company, a subsidiary of which is in a non-complaint business, should also be dubbed as unacceptable, irrespective of its own business activity.

A suggestion has been made that organisations undertaking screening on the basis of shariah-compliance norms should put in place a system requiring compliant companies in industries such as hotels, shipping, etc, which generally tend to fail on one of the criteria for compliance, to regularly report their results and activities to the screening organisation for a fee so that investors could gain a wider choice and the reporting companies not get automatically excluded from the list of shariah-compliant companies communicated to potential investors.

The use of market capitalisation in the screening ratios is inappropriate and should be replaced by other relevant balance sheet items, notably total assets.

The value of the ratio normally set for compliance regarding level of debt financing in relation to total assets, is liberal. It should be scaled down by at least 20 percentage points. Similarly the minimum compliance level for interest income earned needs to be brought down from the normal 5% to 3%, i.e. by about 40%. An additional screen, not usually applied, should also be introduced to control the level of interest-based investments (assets) and it should be set at 10% of the total assets.

Most sets of screening norms include a screen for controlling the level of cash and receivables (or net receivables) on the rationale that these can only be traded at par. A higher proportion of these assets in the total assets, could lead to an infringement of this shariah requirement. It has been shown in the paper that the entire reasoning behind this screen is flawed. Such a screen does not serve any purpose at all as the level of market price of a share is not due to a corresponding value for the company’s cash hoard or receivables and payables. Hence such a ratio is not needed; indeed it is misleading and erroneous.